You may have heard of the NHS Soup and Shake Diet – but what is it really? We break it down in Episode 5 of 10 Minutes to Change.

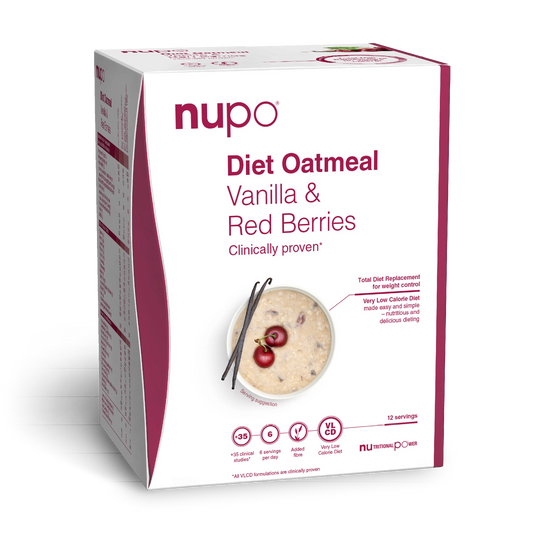

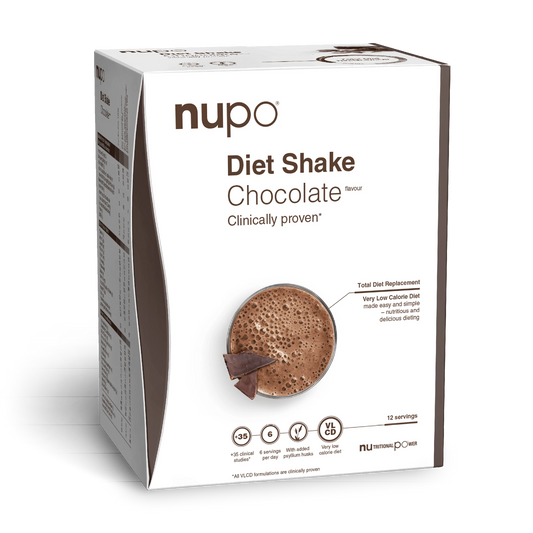

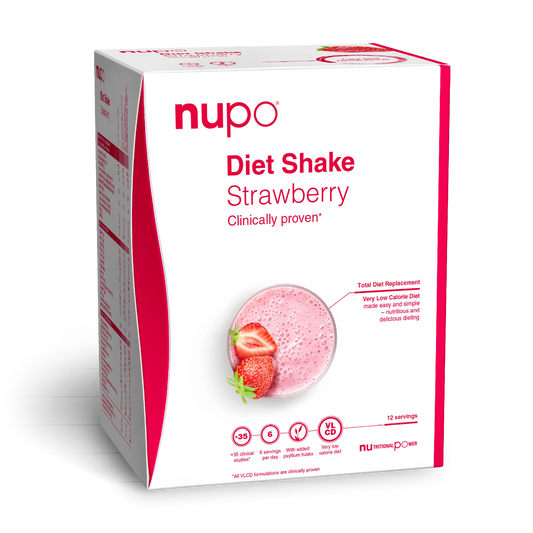

This approach replaces your daily meals with specially formulated soups and shakes – a method supported by research for its impact on type 2 diabetes and significant weight loss. We look at how it compares to other plans, what results people are seeing, and how Nupo fits into the picture. Perfect if you’re exploring 800 calorie diet results or looking for a medically inspired kickstart.

🎧 Hit play to learn if this diet could work for you.

Welcome to 10 Minutes to Change, small steps, big results. In each short episode, we tackle everyday challenges, share practical tips, and explore science-based insights to help you build a clear and balanced lifestyle. Welcome to today's episode where we dive into the world of the soup and shake diet. What is it? How does it work? And why has it gained so much attention in recent years? Whether you're curious about weight management, health, or just want to understand the science behind it, you're in the right place. Let's get started.

We are, uh, cutting through the noise today on a topic that really sits right at the intersection of national policy, health crisis, and, well, personal transformation.

Mm-hmm.

We're talking about the staggering cost of type two diabetes and obesity here in England. Just to put a number on it for you.

Yeah.

The NHS currently spends roughly 10 billion pound every single year just treating diabetes.

That's incredible.

And another 6.5 billion annually treating obesity. I mean, that is a massive financial drain, isn't it?

Uh-huh.

It suggests a clear need for interventions that are not just about management, but maybe truly curative.

Exactly, a different approach.

So today, we are diving into the source material regarding the NHS's potential answer.

Mm-hmm.

The NHS type two diabetes path to remission program. You might know it as the soup and shake diet.

That's the one.

It's been called transformative and, frankly, we need to know if the scale really matches the hype.

Yeah, absolutely. And our mission today is to understand this crucial initiative for you. We'll look at the, um, massive expansion of the program across England just recently. We'll dig into the fascinating science behind the very low calorie diet, the VLCD that seems to make remission possible.

Right.

And of course, the life-altering outcomes being reported—all based on foundational research like, uh, the direct and droplet trials.

Okay, so let's start with that expansion. The first thing that really jumps out in the sources is the sheer scale of the commitment. This is definitely not a small pilot anymore, is it?

No, not at all. The roll-out, which was confirmed in May 2024, it really signals that the NHS believes this could be a national solution.

A big bet.

It's an enormous step up.

Mm-hmm.

They are rolling this program out across the whole of England, essentially doubling its capacity just this year.

Doubling, wow.

Yeah, it's gone from being available in I think 21 local health areas last year to 42 today.

So that means, what, thousands more people?

Exactly. They're targeting over 10,000 more eligible patients right now.

And that level of capacity, well, it requires major investment that must show some serious institutional confidence.

Spot on. Health chiefs are investing 13 million pounds this year alone to support this massive national expansion.

13 million, okay.

And that investment, it really underscores the main goal here, putting type two diabetes into remission.

Which is a huge claim because this condition was historically seen as, you know, chronic, incurable—something you just manage.

Precisely. But this joint initiative, it's between NHS England and Diabetes UK, and it's built on pretty solid clinical evidence that actually for certain patients, remission is absolutely achievable.

Right, which brings us to the crucial part for anyone listening who might be thinking, "Could this apply to me?" Eligibility.

[laughs]

Because this isn't something you can just, uh, sign up for online, is it?

No, definitely not. You need a GQ referral and it's based on quite strict criteria. They're designed to target those specific individuals who are most likely to benefit.

Okay, so what are they?

Well, first, you must be aged 18 to 65 years.

Right.

And crucially, your diagnosis of type two diabetes must have occurred within the last six years.

Ah, so it targets newer diagnoses. Why is that?

It seems the thinking is that in newer diagnoses, the metabolic system might be more likely to respond to this kind of, well, reset.

Interesting. And the criteria are also heavily weighted toward BMI, right?

Right.

But I notice they acknowledge differences based on ethnicity, which seems important.

Yes, that's a key detail. The weight threshold is a BMI over 27 kilogrammer or biohazard for individuals from white ethnic groups.

Okay.

Or a BMI over 25 kilogrammer or bios for those from Black, Asian, and other ethnic groups.

Right. So these criteria ensure the program, which sounds pretty intense, is directed toward the group where weight loss is most likely to drive that metabolic remission.

Exactly. It's about targeting the intervention effectively.

Okay, so let's say someone meets the criteria, gets referred. The core of this 12-month program is that really intensive first 12 weeks.

That's right.

Where people consume strictly 800 to 900 calories a day via these soups, shakes, and bars. Let's be blunt. That sounds like an extreme restriction. How is that physically safe, let alone sustainable for three months?

Yeah, it does sound extreme, and that's where the concept of total diet replacement or TDR is absolutely critical. This isn't just, you know, starving yourself or some fad crash diet.

Okay, how is it different?

The TDR products are very strictly regulated. They have to be. They're formulated to ensure they deliver 100% of all your essential nutrients, vitamins, and minerals daily.

Ah, so nutritionally complete, even at low calories.

Precisely. This allows the system to achieve what's medically known as a very low calorie diet or VLCD at that 800, 900 kilo cal level safely and completely. Sometimes you might also see LCD, low calorie diet, for the slightly higher end, around 900 kilo cal.

Okay, so the TDR and VLCD aspect handles the nutrition safety net, but what about the hunger? I mean, how do participants handle what must be debilitating hunger? That kind of deficit seems impossible to stick to just through willpower.

That's a great question, and it leads to the, well, the elegant scientific mechanism at play here.

Okay.

The VLCD works because it drastically limits carbohydrates. And by doing that, it forces the body into a state we call ketosis.

Ketosis, I've heard of that. Often linked to keto diets.

Exactly. Normally, your body prefers to burn carbs for fuel. When you deprive it of sufficient carbs like on this VLCD, it has to switch strategies. It starts transforming stored fat into molecules called ketones for energy.

Right, burning fat.

Yeah.

Which is the goal for weight loss.

Yes, but the real insight here is the dual benefit of ketosis. You're not only maximizing the burning of fat stores, which drives that rapid weight loss—

Uh-huh

... but the state of ketosis itself has a significant positive side effect, a natural reduction in appetite.

Really? So being in ketosis makes you less hungry?

Generally, yes. This appetite suppression is actually what helps people adhere to the plan during those really intensive 12 weeks. It makes that very low calorie intake manageable in a way it wouldn't otherwise be.

Wow. Okay, so it sounds like the body is essentially sort of tricked into feeling less hungry while it's achieving maximum calorie deficit.

That's a good way to put it.

Which explains why sticking strictly to only those PDR products, the soups and shakes, is absolutely crucial because any outside food, especially carbs, might break that ketosis state—

Precisely

... and bring the hunger roaring back, making it impossible.

Exactly right. Strict adherence isn't just about calories, it's about maintaining that metabolic state. It is the mechanism of action.

Okay. That makes sense.

Okay.

Let's move to the results then because the clinical outcomes reported in the sources are, well, incredibly persuasive. They must be the reason the program is expanding so fast.

The effectiveness is truly striking based on the data reported.

Mm-hmm.

Participants average a loss of 7.2 kilograms. That's over one stone after just one month.

One month? That's fast.

It is. And by the end of the intensive three-month phase, the average weight loss is 13 kilograms. That's over two stone.

13 kilos? Wow. But the goal isn't just weight loss, is it? It's remission. How closely is that massive weight drop, the 13 kilograms on average, correlated with putting diabetes markers like blood sugar back into a non-diabetic range?

It's very directly correlated. The broader clinical evidence, like from the direct trial, shows that substantial weight loss, and they often define that as more than 15 kilograms—

Right

... can lead to type II diabetes remission in up to 86% of individuals who achieve it.

86%? That's huge.

It's remarkable. The NHS program itself, based on its earlier phases, shows early promise for remission in up to half of those who complete the intense phase.

Up to half. Still very significant. If the NHS is spending 10 billion pounds a year treating diabetes, getting even a fraction of people into remission saves a fortune besides changing lives.

Absolutely.

And the sources give this really powerful case study. James Thompson, a 33-year-old from Birmingham, his story kind of puts a human face on these statistics.

His story's pretty monumental, yeah. He started the program at 177 kilograms. That's over 27 stone.

Wow.

And, you know, he apparently struggled initially. The sources say he found the first few months challenging—adjusting to the restrictions and managing medications.

I can only imagine. But the outcome?

The outcome is life-changing. He lost 95 kilograms.

95 kilos?

Yes. Which is 54% of his starting body weight. His diabetes is now reported to be in full remission with an HbA1c level of 29, which is well within the non-diabetic range. He no longer requires diabetes treatment.

That's incredible. Just transformative.

Completely. And beyond just the clinical success, the sources highlight the lifestyle changes. He's taken up cycling. He's walking way more, like up to 30,000 steps some days.

Uh-huh.

He's sleeping better, and he mentioned being able to enjoy things he couldn't before, like finally going on theme park rides with his family, things many of us take for granted.

That really brings it home.

Yeah.

But that anecdote is a powerful illustration of success, yes, but we have to address the reality too. You mentioned he found the first few months challenging.

Yes.

For anyone listening who might be considering this or might be referred, it sounds vital to prepare for what that first week of the VLCD phase actually feels like. It can't be easy.

No, and managing expectations is crucial. It's really important to understand the common and normal experiences during that first week or so.

Okay, so what should people expect?

Well, headaches are very common, especially if someone was previously used to a high sugar intake. It's almost like the body detoxifying.

Right, sugar withdrawal.

Kind of. Then there's dizziness and sometimes feeling chilly. That's often the body just adjusting to the really sharp reduction in calorie intake. You know, going from maybe 2,500 or 3,000 calories a day down to just 800. It's a shock to the system.

Okay, so dizziness, chills. What else?

Fatigue is another big one. The body is literally switching fuel sources, moving away from readily available carbs to breaking down stored fat. That transition takes energy.

So you feel tired even though you're trying to get healthier?

Initially, yes. And of course, there's hunger. That's undeniable in the first few days. The stomach needs time to adjust to smaller volumes.

Right. So wait, the patient is already dealing with cutting their intake by maybe 70%, feeling dizzy, cold, tired. How do the clinicians and coaches actually guide people through what sounds like a pretty brutal first week to stop them from just dropping out?

That coaching and support is absolutely the key to adherence, especially early on. Clinicians preemptively talk about these side effects. They explain they're common, they're temporary.

So knowing it's normal helps.

Hugely. Knowing the headache isn't something sinister, the dizziness will pass, the fatigue is part of the process—it makes it bearable. And the good news is that the intense initial hunger, which is mostly that physical stomach adjustment, usually subsides within about a week.

Oh, really? That quickly.

Generally, yeah. Right around the time ketosis fully establishes itself and that natural appetite suppression starts to kick in properly, consistent communication, reassurance, and support from the clinical team are absolutely essential in that first transitional week.

Okay. So the message is survive the first week basically, and then you get the metabolic reward of ketosis, making it easier.

That's a fair summary, yes.

But remission is only truly valuable if it lasts, right? The sources seem quite clear that maintaining that remission after the program is the real long-term challenge.

Absolutely. That's probably the hardest part. After the initial 12 weeks of TDR, participants enter a really crucial transition phase.

What happens then?

They are still closely monitored by clinicians and coaches, but they start carefully reintroducing healthy, nutritious, real food back into their diet. It's a gradual process.

Because the long-term success isn't really about the shakes and soups. It's about establishing completely new sustainable eating habits to prevent the weight coming back on.

Exactly. You have to fundamentally change the patterns and behaviors that likely contributed to the type II diabetes in the first place. If you just go back to previous routines, the weight regain and potentially the diabetes is likely to follow.

Makes sense. So what's the advice for maintenance? What does that look like?

It's about building a sustainable structure. The recommended maintenance approach often focuses on keeping up that pattern of eating smaller, frequent meals, perhaps three main meals and two or three healthy snacks daily.

So avoiding big blood sugar spikes and crashes?

Precisely, and critically, the advice on food composition is specific. Aim for about half the plate to be vegetables, especially non-starchy, fiber rich ones.

Okay.

Couple that with a good source of lean protein and some whole grain carbohydrates for slow release energy. That kind of plate composition helps manage satiety, delivers nutrients, and keeps glucose levels more stable.

That sounds like generally healthy eating advice, really.

It is, but it requires conscious effort and forming new habits after the intensive phase.

Thanks for listening to 10 Minutes to Change: Small Steps, Big Results where health meets simplicity. Visit nupo.co.uk for inspiration, support, and smart nutrition made for real life. Until next time, take care of you.